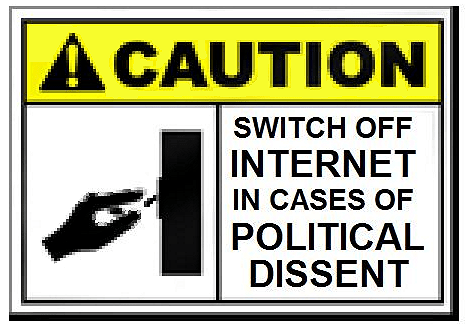

India has seen numerous Internet shutdowns for various reasons in this year, all under the same provision of law – Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC). This section resides as the sole occupant under the chapter of ‘temporary measures to maintain public tranquility’ and gives State Governments the power to issue orders for immediate remedy in urgent cases of nuisance or apprehended danger. However, the increasing use of this provision to completely shut down the Internet is becoming a cause of concern, for the reason that it amounts to a direct violation of the fundamental right to freedom of speech guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India.

The Internet is not only a medium to exercise the right to free speech and expression, but is correctly identified as a catalyst in the process of imparting, receiving, and sending information. This freedom is undisputedly fundamental for a democratic organization, moreover it is an enabler of other socio- economic and cultural rights. Similarly, the Internet is highly instrumental in facilitating a wide range of rights by providing a revolutionary platform in realization of free speech. Frank La Rue, the Special Rapporteur on protection and promotion of the right to freedom of opinion and expression appointed by the United Nations, while focusing on the point made above, also highlighted the changing nature of this right in relation to Internet proliferation in his report dated 16 May 2011. Furthermore, while addressing concerns about censorship, the Special Rapporteur noted that arbitrary blocking of complete Internet services is a disproportionate action in any situation. Internet shut down even with justification, negates the possibility of targeted filtration of content and would render inaccessible even content that is not illegal.

In this post, we aim to understand the legal position accorded to Section 144 CrPC, its relation with Article 19 of the Indian Constitution, and its increasing usage as a provision to shut down the internet services.

Dissecting Section 144

From a bare reading, the relevant portion of Section 144 can be carved out into three basic elements:

-

The authority to issue orders: lies with the District Magistrate, a sub divisional magistrate or any other Executive magistrate specially empowered by the State Government in this behalf.

-

The grounds on which S. 144 can be invoked: The reasons include: a)sufficient ground, b) requirement for immediate prevention, and c)speedy remedy to prevent a likely obstruction, annoyance or injury to any person lawfully employed, or danger to human life, health or safety, or a disturbance of the public tranquility, or a riot, or an affray.

-

The intended recipient: After determining sufficient ground and through a written order, the authorized can direct any person to abstain from a certain act or to take certain order with respect to certain property in his possession or under his management.

Between 2013 and 2015, Internet services have been completely shut down in certain parts of India around seven times, where five of them happened in the year 2015 alone. In 2013 and 2014, Internet services were banned in parts of Kashmir and Gujarat respectively. 2015 started with an Internet blackout in Nagaland in March to restrict circulation of a lynching video of a rape accused, followed by parts of Gujarat being cut off in late August. Manipur and Kashmir were disconnected in September owing to violence in a small town of Chudandrapur and prohibition on cow slaughter respectively. More recently in December, Rajasthan experienced an Internet shut down in 11 districts.

The Supreme Court in case of Madhu Limaye and Anr v. Ved Murti and Ors. ((1970) 3 SCC 746), has held that the scope of Section 144 extends to making an order which is either prohibitory or mandatory in nature and ‘urgency’ is the only criteria that can justify an order under this Section. With the wide range of powers granted to the State government, including the power to grant the order ex parte, the ambit of this provision has been mostly used to curb unlawful assemblies and processions that are anticipated as a danger to public tranquility. This vaguely worded provision, that includes terms like ‘annoyance’, was constitutionally challenged in the Supreme Court in 1970, but retained its place when it was held that the likelihood of its misuse is not a reason enough for it to be struck down. Even though the appointed authorities have the discretion to decide the measures required to curb a situation, their actions are not protected from judicial review. The Supreme Court in the case of Ramlila Maidan Incident v. Home Secretary, Union of India & Ors. ((2012) 5 SCC 1), illustrated that the degree of threat involved for the use of this provision need not be ‘quandry, imaginary or a merely likely possibility, but a real threat to public peace and tranquility.’

Although in the past this provision has been extensively used to break unlawful assemblies, rarely has any communication system, except for the Internet been threatened by the overreaching power made available under this section. A blanket ban on Internet services, mobile/broadband or both, is an order given to a person, in this case the Internet Service Provider (ISP), who holds the reigns to this service. Although a general order is justified under this section, it has traditionally been used to issue orders directed at particular persons or groups . The Apex Court clarified in the case of Madhu Limaye and Anr. v. Ved Murti and Ors. that if the action sought by the empowered authorities is too general in its scope, legal remedies of judicial review should be claimed.

The Internet is not merely a communication system, but is the chosen platform for business and e- commerce, e- governance programs, a site for research and information, among many other things. Consequently, a complete shut down of the Internet has implications for the entire population of that area, which includes innocent people who have no role in causing the apprehended danger or nuisance. This in turn causes wide spread censorship and a violation of citizens’ fundamental right to free speech and expression under Article 19 (1)(a) of the Constitution as it prohibits the sending, receiving, and dissemination of information.

Relationship of Section 144 & Article 19 (1)(a)

The freedom of speech and expression that is enshrined in Article 19 (1)(a) of the Indian constitution has been given a plethora of titles by the Supreme Court including, Ark of the Covenant of democracy, and market place of ideas. It has also been rightly established that this right is not absolute and can be curtailed based on reasonable restrictions such as ‘in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence’ as enumerated in Article 19(2) of the Constitution.

Over the years, a rich and elaborate jurisprudence has developed around this fundamental right. Since the inception of the Constitution, the Supreme Court has interpreted and devised suitable tests to prevent the unlawful restriction of Article 19(1)(a), articulating the degree of reasonableness and adequacy of measures required and nuanced difference between different types of speech.

The Apex Court has rightly held that the guaranteed freedom of free speech and expression can be restricted only if a danger qualifies as an immediate threat as per Article 19(2). This danger should not be ‘remote, conjectural or far fetched, but have a proximate and direct nexus with the expression sought to be restricted‘. In the context of Section 144 CrPC, the Supreme Court mentioned that along with the test of direct and proximate nexus, the State Government has a duty to ensure that the measures imposed for restricting this right are least invasive in nature and also unavoidable in the given circumstance. The type of speech that can be restricted was clarified by the Supreme Court in the recent landmark judgment of Shreya Singhal v. Union of India ((2015) 5 SCC 1). While highlighting the subtle difference between discussion, advocacy, and incitement, it was held that only speech that may lead to ‘incitement’ can justifiably be curtailed under Article 19(2). Therefore, when this right is restricted, firstly, there has to be surety of a looming danger that has a ‘direct and proximate nexus’ with the expression being curtailed, secondly, this expression needs to qualify as ‘incitement’ and not mere advocacy of one’s opinion, and thirdly, the measure imposed should be the last resort and unavoidable.

Section 144 is a temporary remedy, under which an order is valid only for a period of two months as per sub-section 4 of this provision. This order can be extended to a further period of six months if the State Government deems it necessary to prevent riot, affray, or for the health and safety of citizens. An order under this section is prohibitory in nature, and the Supreme Court has differentiated between measures that have a ‘prohibitory’ and ‘restrictive’ effect. It has pointed out, that the words ‘prohibition’ and ‘restriction’ cannot be used interchangeably. The threshold for ‘prohibiting’ a particular activity is higher and must indeed satisfy the requirement that ‘any lesser alternative would be inadequate.’ Hence, though, the use of this particular section has been validated in times of emergencies, where actions are taken at the discretion of the empowered authorities, these measures cannot be excessive or arbitrary.

Internet, Free Speech & Section 144

The shut down of mobile internet services caused an uproar by the effected parties and civil society activists and this action taken under Section 144 was challenged in the Gujarat High Court as a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in Guarav Sureshbhai Vyas v. State of Gujarat (W.P. (PIL) No. 191 of 2015). It contended that the power to block certain information on an online/computer related forum was given in Section 69A of the IT Act, hence the State Government was not competent to use Section 144 CrPC to restrict the use of internet. Section 69A, along with the Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009 provide for a mechanism to block information from public access through any computer resource by a direction from the Central Government or any officer specially authorized in this behalf. This direction is only to be given when the officer deems it necessary or expedient, and ‘in the interest of sovereignty and integrity of India, defence of India, security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states or public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of any cognizable offence relating to the above.’ The procedure for issuance of this order is laid down in the above mentioned rules where the effected party is given a reasonable opportunity to be heard as per Rule 8(1).The final order given for such blocking to a Government agency, or intermediary has to have its reasons recorded in writing as stated under Section 69A(1) of the IT Act.

While delivering the judgement for the case challenging the authority behind shut down of mobile internet in Gujarat, the Gujarat High Court defended the State Government’s authority under Section 144 CrPC. It held that the state government is a competent authority under this provision and it depends upon their discretion to exercise the power with prudence, public duty and the sufficiency of action in their view. Furthermore, the court refrained from exercising appellate power to decide upon the ‘sufficiency of matter to exercise power under Section 144’. It limited its decision on if there was an ‘arbitrary exercise of power (by the state government) without any objective material.’ The petitioners in this case argued for the use of Section 69A to block specific social media websites, through which the messages apprehended to cause violence were being spread. The court, disregarding this point, maintained that the scope of operations of Section 69A and Section 144 were different and overlapped, only to cover ‘public order’. The court concluded that state government, which had the rightful authority in times of emergency, deemed fit to block entire mobile Internet services, failing which, the situation would have worsened.

This judgement rests its reasoning on the ‘discretionary’ power and ‘objective material’ found by the government of Gujarat for a complete mobile Internet shut down in the state for over a week. At this point, it is important to recall the Supreme Court’s pertinent judgement in the case of Ramlila Maidan Incident v. Home Secretary, Union of India & Ors wherein it was highlighted that Section 144 is to be used as a last resort, when ‘a lesser alternative would be inadequate.‘ In the present judgement, pulling the plug on mobile internet was not the Gujarat Government’s last resort. The state government ignored the option of making a request to the nodal officer designated by the Central Government under Section 69A to specifically block the social media websites, like Facebook, Whatsapp, Twitter that were reportedly used by Mr. Hardik Patel to communicate with the public and spread this propaganda for inciting caste based violence in the State.

The importance of Internet is not limited as a platform for exercising freedom of opinion and expression, but over the years, it has also entrenched every aspect of the society; from business models, communication systems, education, transport facilities, and research and information to name a few. Apart from the legal lacunae in the judgement of Gujarat High Court, the state of Gujarat also recorded heavy losses suffered by businesses during the shut down. The e-commerce businesses, web based or application based, cab companies, bank services, hotel and travel services were among the major categories of businesses that were drastically hit during the shut down of mobile Internet in the state of Gujarat for over a week in August, 2015. This sector, especially start-ups have become immensely integrated and dependent on the internet for their orders, delivery notifications. They make use of mobile applications to make it convenient for consumers to buy their products. Furthermore, businesses who sell their commodities on platforms like Flipkart, eBay, Amazon complained of losses and were concerned about customer satisfaction from their products because the extent of their sales depend on customer reviews and ratings, and a delay in delivery or notification may not fare well for their record. In one week of mobile Internet being cut off for Gujarat, these e-commerce websites and applications recorded a drop of 90% in their businesses.

Apart from e-commerce, banking services accrued a loss worth Rs. 7,000 crore in one week due to the inability to conduct transactions, especially in businesses that are dominated by the use of credit/debit card. As SMS services were also blocked during this time, generating OTPs (One Time Password) to facilitate the process were also disabled. Moreover, the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) claimed that telecom operators that deal with internet services were also significantly hit and incurred losses of Rs. 30 crore in this short period. One private telecom operator in Vadodara, who provided 3G internet services exclaimed that his losses ran into Rs. 25 lakh per day for the period when mobile internet was cut off. The heavy losses accrued by business due to this untimely shut down of the internet also amount to an infringement of their freedom ‘to practice any profession, or to carry on any occupation, trade or business’ as laid down under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution. This fundamental right can only be limited on the following three grounds as laid under Article 19(6):

-

Reasonable restrictions in the interest of general public;

-

Any law relating to the professional or technical qualifications necessary for carrying on any profession, trade, or business; and

-

Any law relating to the carrying on by the State, or by a corporation owned or controlled by the State, of any trade, business, industry or service, whether to the exclusion, complete or partial, of citizens or otherwise.

The phrase ‘in the interest of general public’ has been held to include ‘public order, public health, public security, morals, economic welfare of the community and the objects mentioned in Part IV (Directive Principles of State Policy) of the Constitution.’ In the present scenario, due to a restriction in accessing the internet, businesses that rely on the internet as their operating medium were unduly constrained, and incurred significant monetary losses, thereby affecting their fundamental right to practice any profession, or carry on with any trade, business or occupation.

Internet fosters the burden of being a platform for exercising the right of freedom of speech and expression, along with acting as the backbone for a growing economy. The power under Section 144 CrPC is to be used with caution and only when there is ‘an actual and prominent threat endangering public order and tranquility‘; it should neither be arbitrary, nor subvert the rights protected by the Constitution. Similarly, restriction of free speech is also qualified by the direct and proximate nexus of the expression to the danger sought to be prevented. Moreover, as has been clarified by the Supreme Court, Section 144 and the restriction on free speech should only be used as the last resort, when a lesser invasive alternative is not available. Section 144 is a means to curb apprehended danger and nuisance in emergencies, but its use to ban Internet access for a region is an excessive and arbitrary use of powers granted to the state government under this provision. Additionally, a complete shut down of this system is a monumental restriction on the guaranteed right of free speech and expression. Therefore, pulling the plug on entire Internet under Section 144 of CrPC is not only a colossal violation of Article 19 of the Indian Constitution, but is also not the rightful use of powers under Section 144 of CrPC.

UPDATE: A Special Leave Petition (SLP) challenging the order of the Gujarat High Court in the case of Gaurav Sureshbhai Vyas v. State of Gujarat on the use of Section 144 for internet shut downs was dismissed by the Supreme Court on 12th February, 2016. While upholding the power of the state governments to restrict access to internet, Chief Justice T.S Thakur remarked that “It becomes very necessary sometimes for law and order.”